Consumer's Surplus:

Definition and Explanation:

The concept of consumer’s surplus was introduced by Alfred

Marshall. According to him:

"A consumer is generally willing to pay more for a

given quantity of good than what he actually pays at the price prevailing in the

market".

For example, you go to the market for the purchase of a pen. You are

mentally prepared to pay $25 for the pen which the seller has shown to you. He

offers the pen for $10 only. You immediately purchase the pen and say ‘thank

you’.

You were willing to pay $25 for the pen but you are delighted to get it for $10

only. Consumer’s surplus is the difference between the maximum amount a consumer

is willing to pay for the good and the price he actually pays for the good. In

our example given above, the consumer’s surplus is $15 ($25 – $10).

Demand

Curve and Consumer’s Surplus:

The consumer surplus can be easily found out by consumer’s demand curve for the

commodity and the current market price which we assume a purchaser cannot

change. In the words of Alfred Marshall:

“The excess of the price which he (consumer) would be willing to pay rather than

go without the thing over that which he actually does pay is the economic

measure of this surplus satisfaction”.

In the words of A. Koutsoyannis:

“Consumer’s surplus is equal to the difference between the amount of money that

consumer actually pays to buy a certain quantity rather than go without it”.

The concept of consumer’s surplus is the result of two important phenomena:

(i) Characteristic of consumer’s behavior.

(ii) Characteristic of market.

The characteristic of consumer’s behavior is that as he buys more and more of a

particular commodity, the marginal utility of the successive units begins to

decrease. A rational buyer continuous purchasing the commodity up to the unit

which equates his marginal utility of the good to the price he pays for it.

The second phenomenon is that there is perfect competition among sellers and a

single price prevails in the market for a particular commodity at a particular

time. The buyer is able to get the first unit of the commodity at the same price

as the second or pay any other unit thereafter.

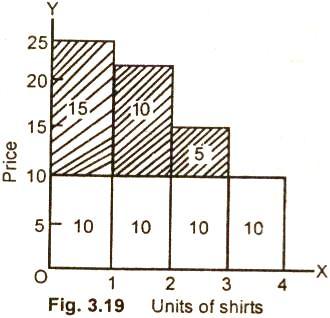

Schedule:

The concept of consumer’s surplus is now explained with the help of a schedule

and a demand curve.

|

Quantity |

Willing to Pay ($) |

Price ($) |

Consumer’s Surplus ($) |

|

1 |

25 |

10 |

15 = (25 – 10) |

|

2 |

20 |

10 |

10 = (20 – 10) |

|

3 |

15 |

10 |

5 = (15 – 10) |

|

4 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

|

Total |

75 |

10 x 4 = 40 |

30 |

Diagram/Figure:

In this figure 3.20, the individual demand curve DD/ shows the

maximum amount a consumer is willing to pay for each unit of the good. An

individual is not willing to purchase any pen at a price of $30 per month. He

will, however, is willing to purchase one pen at a price of $20 per pen, he is

willing to purchase 2 pens. The surplus diminishes with the decline in the

marginal utility of pens.

In case the price comes down to $15 per pen, the consumer purchases 3 pens. By

using this demand curve, we measure the surplus which a consumer gets from the

purchase of pens. The current market price of a pen $10, which we have assumed

the purchaser cannot change. The consumer was willing to pay $25 per pen but he

actually pay $10 only, the consumer’s surplus for the first pen is $15 = (25 –

10).

For the second pen, it is $10 = (20 – 10) and for the third consumer’s surplus

is $5 = (15 – 10).

There is no surplus on the fourth unit as the market price for the pen is the

same what he would have paid for the pen. The total consumer’s surplus from the

purchase of four pens is $15 + $10 + $5 = $30. It is the sum of surpluses

received from each pen. The shaded area in the graph shows the total consumer’s

surplus.

Criticism:

The Marshallian concept of consumer’s surplus has been severally

criticized by modern economists Allen and Hicks. According to them, the concept

is based on assumptions which are unwarranted. Utility, according to them, is a

psychological feeling. It cannot be exactly measured in term of money.

In Marshallian analysis, the marginal utility of money is assumed to remain

constant. The fact is that when a consumer spends money on goods, his income

decreases and the marginal utility of money to him rises. Analysis ignores this

basic fact.

Consumer’s surplus is said to be imaginary as it assumes that utilities derived

from various goods are independent. In real life, this is not true. The fact is

that utilities derived from various goods are independent.

Measurement of Consumer’s Surplus with the Help of Indifference Curves (Hicksian

Method):

Professor J.R. Hicks, has explained the concept of consumer surplus with the

help of indifference curve technique . According to Hicks when there is fall in

the price of a commodity, it has two main effects:

First, the consumer can purchase more of the good whose price has fallen.

Secondly, he can purchase the same quantity of the good as he was buying

before but with a lesser amount of money. He spares some money in the bargain.

This is a form of rise in the real income of the consumer.

Diagram/Figure:

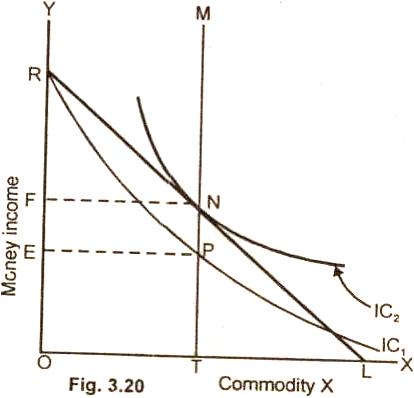

The Hicksian method of measuring consumer’s surplus is now explained with the

help of diagram below.

In figure 3.20 commodity X is measured on OX axis and money income of an

individual on OY axis. We assume here that a consumer does not know the price of

the commodity X and has OR quantity of money. The indifference curve IC1

represents various combinations of income and X of commodity X which yield the

same level of satisfaction to the consumer.

The indifference curve IC1 originates from point R. It shows the

stage when the consumer retains all of his income and zero units of commodity

for a given level of the utility. The consumer moves down along the curve IC1.

The consumer at point P buys OT amount of commodity X and has OE amount of money

income. In other words, the consumer is ready to sacrifice RE amount of money

for getting OT units of commodity X.

We now assume that the consumer is informed of the price of commodity X. The RL

is the budget line. The budget line touches the indifference curve IC2

at point N which is the point of equilibrium. The consumer now has the OT

commodity of X and OF amount of income. He gives up RF amount of money to buy OT

units of commodity X. Previously he was ready to pay RE amount of income which

is higher than the amount he pays now. We infer from this that RE – RF i.e., FE

is the consumer surplus.

FE is the difference between the amount of income the consumer was willing to

pay and what he actually pays. The surplus has also shifted the consumer on the

higher level of satisfaction from IC1 to IC2.

Importance of Consumer’s Surplus:

The concept of consumer’s surplus has both theoretical as well as practical

importance.

(i) Theoretical importance: The idea of consumer’s surplus reveals the

benefits which we derive from our purchase of the commodity in the market.

For example, when we purchase salt, or a match box, we are willing to pay

the amount much higher than their market value. For example, a consumer would be

willing to pay $10 for a match box rather than go without it but he actually pay

Re one only on the purchase of a match box. Consumer’s surplus on the purchase

of match box thus is $ 9.0.

(ii) Practical importance: A monopolist can charge higher price for his

product if the consumers are enjoying large consumers surplus on the use of his

product.

(iii) The inhabitants of a country derive consumer's surplus when they

import commodities from abroad. They are usually prepared to pay more for than

what they actually pay.

(iv) A finance minister imposes taxes of the commodities yielding consumer's

surplus.

(v) An entrepreneur before investing capital in a project evaluates the

consumer's surplus to be derived from it. If the benefits to the obtained are

greater than the costs, the investment is undertaken.

Relevant Articles:

|